How Currencies Collapse, Part 2: Money Evolves and Currencies Fail

In Part 1 of this series, I said that, for the sake of convenience, I would treat the terms currency and money as meaning the same thing. Most people use the terms interchangeably. But I also assured the readers that they are not the same, and that I would spell out the difference.

The Critical Distinction Between Money and Currency

The distinction is important, especially in the overall context here. A currency collapse can happen and, historically, it has happened many, many times; money cannot collapse. Money stores purchasing power. Currency lets it slowly erode.

Money is what humans invented when they realized that trade via barter wasn’t going to work anymore. Barter was clumsy. It required someone to have something you wanted at the same time you had something they wanted. Both parties also had to agree that the items were of equivalent value.

The obvious need was an intermediary, so some enlightened soul came up with the general concept of money. The seller would get some token back from the buyer that could be applied to a purchase later on. Over the ages, different cultures tried a wide variety of things as money: furs, shells, salt, beads, the list goes on. All of them had insoluble problems.

The Rise of Precious Metals as Money

Precious metals were revered in ancient Egypt, 5,000 years ago. But they were not turned into what we now know as money until around 700 BCE, when the first coins were minted. Gold and silver were chosen because they possessed all the characteristics money had to have. They could serve as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. They were portable, durable, divisible, convenient, fungible, rare, and difficult to produce. They had inherent value.

And so it was for over a millennium and a half. Precious metals made for stable money. As I noted in part 1 with regard to Rome, governments could and did cheat on a gold or silver coin’s content. But for the most part, coined money was popular and the system worked. Plus, because of the universal high esteem in which gold and silver are held, they never become worthless. Real money can’t collapse.

The Advent of Paper Money and the Ensuing Collapse

Then there was a major change, in China in 1160 CE. At the time, the Song Dynasty was near bankruptcy, so it began issuing promissory notes that could be redeemed for coins. That must have seemed like the first great leap forward. Now you could carry a fortune in your pocket, and soldiers could be paid in cheaply produced paper instead of money.

These notes, known as huizi, were the first government-issued paper currency in history. Note the critical shift: they were not money but were a claim on money. Instead of an actual coin in hand, all you had was a governmental promise of redemption.

Every note was supposed to be backed by sufficient coins, held in storage, that users could freely exchange for. Guess what happened. That’s right, just like the Romans hundreds of years earlier, the government cheated. Only instead of adulterating their coins, they printed notes far in excess of the metal reserves needed to cover them.

Result: terrible inflation and, ultimately, history’s first paper currency collapse.

The Goldsmiths and the Origins of Modern Banking

Back in Europe, in the 17th century, gold had become accepted as a primary measure of wealth, and those who had a lot of it needed someplace to keep it. Home and businesses weren’t safe. There were no banks. Where did you find the nearest secured vault?

With the only guy in town who had one, the local goldsmith. For safety’s sake, merchants in Great Britain began depositing their gold there, for a fee. The goldsmith would then issue a claim check. Similar to what the Chinese did, except that the promissory note was created by a private party, not the government. People soon figured out that it was much less of a hassle to pay for things by just handing over their claim check to settle a transaction, rather than retrieving their physical gold. Thus the notes started circulating as currency. They were trusted, being fully backed by the goldsmith’s holdings in the vault.

The Legacy of Fractional Reserve Banking

You know what comes next, right? Yeah, they cheated. The goldsmiths padded the profit from their storage fees by creating extra claim checks for which no gold existed. This was safe to do until large numbers of their depositors demanded their gold back at the same time (later to be called a “bank run”).

Goldsmiths’ notes would die out, but the concept would eventually be embraced by both private banks and governments worldwide. It would endure for centuries. Numerous currencies came (and largely went). But users were always assured that somewhere there was a vault that contained enough gold or silver to redeem all of the paper certificates. Most of the time, it was a lie.

The practice even got a fancy name that made it sound legit. When a government or central bank issues unbacked currency, that’s known as a fractional reserve system. It has survived into modern times—and reached unimaginable heights.

The Modern Era of Currency and Its Challenges

The history of money/currency here in the U.S. is a fascinating topic, but way too broad to cover here. So let’s fast forward to the early 20th century and passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913.

Previously, the dollar was 100% gold-backed. You could take your $20 gold certificate to the bank and exchange it for a $20 gold coin. Under the Fed, however, the U.S. adopted a “partial” gold standard—or fractional reserve—in which currency was only required to be 40% backed by gold.

You could still swap certificates for coins, dollar for dollar, but I’m sure you can see why those days were numbered. For every $20 in gold in the Treasury’s vaults the Fed could now circulate $50 worth of certificates, which were merely promissory notes for gold. As noted in Part 1, this is monetary inflation, which swells the amount of currency in circulation, concurrently devaluing it.

Sure enough, just 20 years later, FDR ordered the abolition of paper-to-gold conversion. Gold certificates were no longer honored, instead converted to Federal Reserve Notes, backed by nothing. FDR also changed the statutory price of gold from $20.67/oz. to $35. As a result, holders of the old currency had to take a near-70% haircut in value when they were forced into the new Notes. The country then went on a quasi-gold standard—where foreign nations could still get gold for their dollars, but American citizens couldn’t.

The quasi-gold standard ended in 1971, after some countries lost faith in the buck and initiated a massive outrush of gold from the U.S. With stockpiles of the metal dwindling, President Nixon ended all convertibility, “closing the gold window” for good. It was the biggest default on financial obligations the country had seen since FDR abolished gold dollars. Foreigners who’d been promised gold for their USD were told they were out of luck.

It was a currency collapse, of sorts. But since the USD remained the world’s primary trade currency, the effects were not disastrous. Yet. That doesn’t mean there weren’t dire consequences, however. If you want to see them presented visually, just go to https://wtfhappenedin1971.com/

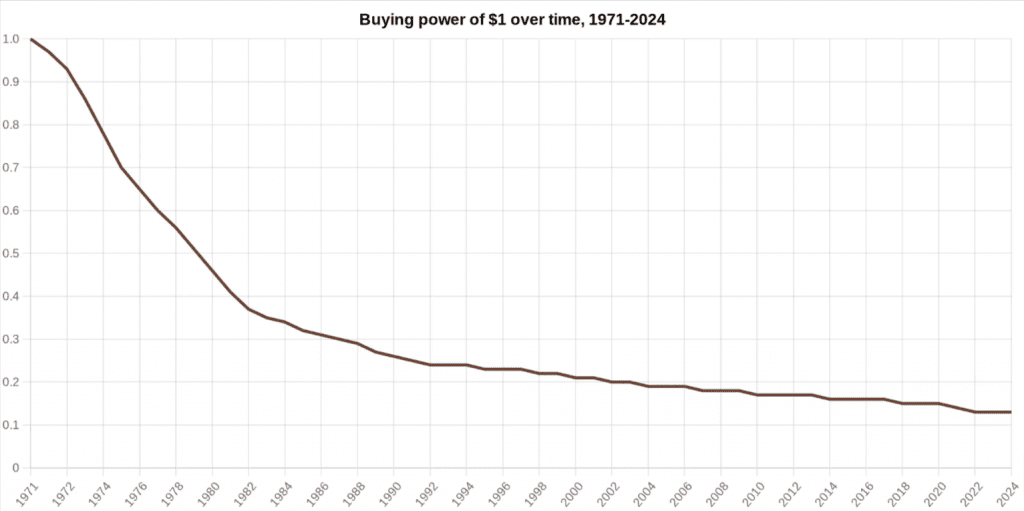

Suffice it to say that you only need look at price inflation, which means your currency’s value is going down. $1 in 1971 is equivalent in purchasing power to about $7.71 today. This means that today’s prices are 7.71 times more expensive than average prices in 1971, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. A dollar today only buys 12.97% of what it could buy back then. This is what that looks like graphically:

Looks awful, and is. But the graph is actually a bit misleading, because of the scale. The high-drama 60% decline during the stagflation of the ’70s makes the rest look more tame, smoothing the curve. See that little dip at the end? It appears innocuous. It wasn’t. Obscured is the fact that your buying power declined by an alarming 20% between 2020 and 2024. (Or, if you’re like me, probably more.) Why? Largely because the government handed out $2.5 trillion in “stimulus” funds it didn’t have.

What you’re really looking at, folks, is a slow-motion currency collapse. Do not fear, the Federal Reserve tells us, we’ve got this under control. Do they? Well, they’d better. In the next posts in this series, we’ll consider whether this could turn into a full-blown, falling-off-a-cliff catastrophe.

By Doug Hornig

Contributing Author, ITM Trading

www.itmtrading.com

P.S. Worried about the impact of inflation and unstable monetary policies on your financial security? Don’t wait until it’s too late! For over 28 years, we’ve guided thousands in safeguarding their wealth and securing their retirement against potential currency collapses. Schedule your free consultation today to explore protective strategies tailored for you. Call 866-953-7929 or click here to schedule your consultation now.